Loser to lady-killer, listen up.  This advert is for a Daihatsu, a functional, spacious, yet very uncool car. “Family men” needing something to drive for the school-run typically purchase it, so it definitely lacks the sexy reputation of an Audi or the flashy displays of wealth from a Lamborghini. Yet this is a very entertaining advert, as it uses humour, and taps into the sort of person that the customers of this model want to be, whilst at the same time pointing out the main desirable feature of the car- how spacious it is. They know that this car won’t fulfil all their lady-killing desires, but this advert includes them in a personal “in-joke,” whilst saying “but seriously, I can hold five children, a buggy, two suitcases, eleven lunch boxes, two dozen toys, six bricks of Lego, and your wife.” There is a huge amount of support for humour in advertising. Sternthal & Craig (1973) explained that humour works in advertising because it creates a positive opinion of the source, resulting in a positive mood in the audience, making them more susceptible to persuasion. Worth & Mackie (1987) exposed students in either a good mood or a neutral mood to either a pro-attitudinal or counter-attitudinal message comprised of either strong or weak arguments. They found that participants who were in a good mood exhibited more signs of reduced systematic processing (an advertisers goldmine), and more attitude change than those in a neutral mood. Furthermore, their responses showed less of a contrast between strong and weak messages than those in the neutral condition. This is excellent news for the Daihatsu, as it means that the humour used in the campaign may lessen the contrast between this model and a better one. Sternthal & Craig (1973) also claim that humour attracts attention, which makes the car more memorable. The availability bias therefore ensures we have this car in the forefront of our minds. Schwartz et al. (1991) demonstrated that participants who were asked to recall six examples of their own assertive behaviour rated themselves as more assertive than those who were asked to recall twelve examples. This is because the condition where they had to recall twelve examples was much harder to do. It can therefore be concluded that if a car was easy to recall due to a humorous advert, people may rate it more highly as they might assume that if it weren’t a good car, they would not have spent so much time thinking about it. Finally, Sternthal & Craig (1973) argue that humour may distract the audience meaning that they are less likely to produce counter-arguments against the message. In the example at hand, the audience could argue that they want a car that is a little sexier than the Daihatsu, however because its’ uncool reputation has been acknowledged in its own advertising campaign, it is protected by a humorous buffer. To conclude, if you actually want to be a lady-killer, this is not the car for you. However if you are ever in the position of having to sell this sort of car, or indeed yourself (e.g. want to ask someone out, but are certain they are out of your league), humour is the way forward. It creates a positive opinion of the source, a positive mood in the audience, will be memorable and therefore easy to recall, and distracts the audience from all the negatives (e.g. a dodgy haircut or the fact you live in your mum’s basement). Good luck. References Sternthal, B., & Craig, C. (1973). Humour in Advertising. Journal of Marketing, 37(4), 12-18. Worth, L., & Mackie, D. (1987). The cognitive mediation of positive affect in persuasion. Social cognition, 5(1). Schwarz, Norbert; Bless, Herbert; Strack, Fritz; Klumpp, Gisela; Rittenauer-Schatka, Helga; Simons, Annette (1991). “Ease of retrieval as information: Another look at the availability heuristic”. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 61 (2): 195–202.

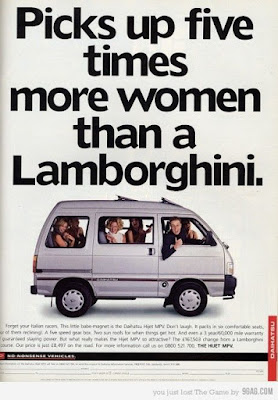

This advert is for a Daihatsu, a functional, spacious, yet very uncool car. “Family men” needing something to drive for the school-run typically purchase it, so it definitely lacks the sexy reputation of an Audi or the flashy displays of wealth from a Lamborghini. Yet this is a very entertaining advert, as it uses humour, and taps into the sort of person that the customers of this model want to be, whilst at the same time pointing out the main desirable feature of the car- how spacious it is. They know that this car won’t fulfil all their lady-killing desires, but this advert includes them in a personal “in-joke,” whilst saying “but seriously, I can hold five children, a buggy, two suitcases, eleven lunch boxes, two dozen toys, six bricks of Lego, and your wife.” There is a huge amount of support for humour in advertising. Sternthal & Craig (1973) explained that humour works in advertising because it creates a positive opinion of the source, resulting in a positive mood in the audience, making them more susceptible to persuasion. Worth & Mackie (1987) exposed students in either a good mood or a neutral mood to either a pro-attitudinal or counter-attitudinal message comprised of either strong or weak arguments. They found that participants who were in a good mood exhibited more signs of reduced systematic processing (an advertisers goldmine), and more attitude change than those in a neutral mood. Furthermore, their responses showed less of a contrast between strong and weak messages than those in the neutral condition. This is excellent news for the Daihatsu, as it means that the humour used in the campaign may lessen the contrast between this model and a better one. Sternthal & Craig (1973) also claim that humour attracts attention, which makes the car more memorable. The availability bias therefore ensures we have this car in the forefront of our minds. Schwartz et al. (1991) demonstrated that participants who were asked to recall six examples of their own assertive behaviour rated themselves as more assertive than those who were asked to recall twelve examples. This is because the condition where they had to recall twelve examples was much harder to do. It can therefore be concluded that if a car was easy to recall due to a humorous advert, people may rate it more highly as they might assume that if it weren’t a good car, they would not have spent so much time thinking about it. Finally, Sternthal & Craig (1973) argue that humour may distract the audience meaning that they are less likely to produce counter-arguments against the message. In the example at hand, the audience could argue that they want a car that is a little sexier than the Daihatsu, however because its’ uncool reputation has been acknowledged in its own advertising campaign, it is protected by a humorous buffer. To conclude, if you actually want to be a lady-killer, this is not the car for you. However if you are ever in the position of having to sell this sort of car, or indeed yourself (e.g. want to ask someone out, but are certain they are out of your league), humour is the way forward. It creates a positive opinion of the source, a positive mood in the audience, will be memorable and therefore easy to recall, and distracts the audience from all the negatives (e.g. a dodgy haircut or the fact you live in your mum’s basement). Good luck. References Sternthal, B., & Craig, C. (1973). Humour in Advertising. Journal of Marketing, 37(4), 12-18. Worth, L., & Mackie, D. (1987). The cognitive mediation of positive affect in persuasion. Social cognition, 5(1). Schwarz, Norbert; Bless, Herbert; Strack, Fritz; Klumpp, Gisela; Rittenauer-Schatka, Helga; Simons, Annette (1991). “Ease of retrieval as information: Another look at the availability heuristic”. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 61 (2): 195–202.

Why did I just buy a jumpsuit I am not sure I even want?

For anyone who knows me, I am IN LOVE with online shopping. Most of my student loan goes into funding my ‘hobby’ and it is one I am so not ashamed off. Online shopping really kicked off around 2003 (“The History of Online Shopping in a Nutshell”, 2010) when Amazon posted their first yearly profit, although it had been around prior to this; and it was only a few years after this it found a place in my heart…I think it all started when I was 8 and watched my dad buy our new trampoline online. I was sat with him and helped him choose it and I was SO excited for it to arrive. This excitement got even greater when he told me we didn’t even have to go to the shops to pay for it, his little plastic card had done it for us! The trampoline was to arrive in a week or so. My dad probably regrets letting me sit in on the purchase, for about 4 months afterwards I was buying toys online and getting them delivered home with his ‘little plastic card’. I obviously pretended I had nothing to do with the strange packages arriving at home most weeks, but soon enough I was caught out. Online shopping is great, you don’t have to traipse around the shops getting hot and bothered trying to find an outfit that might not even be there; everything the store has to offer is on one handy web page. As the old ‘endowment effect goes’ – consumers value products more once they actually own it, and simply touching an item may increase a shopper’s sense of ownership and compel the consumer to buy the product (Gregory, 2009). An Ohio State University study demonstrated this effect using coffee mugs (Wolf, Arkes & Muhanna, 2008): Participants were shown an inexpensive coffee mug and allowed to hold it for either 10 or 30 seconds. They were then allowed to bid for the mug in a closed (bids cannot be seen) or open (bids can be seen) auction. Before bidding, the participants were told the retail value of the mug ($3.95 in closed auction, $4.95 in open auction) Results = People who held the mug for longer bid more Results = People who held the mug for 30 seconds bid more than the retail price 4 out of 7 times However, with online shopping you don’t even come close to the product, so how do they persuade us to buy anything? This was answered for me a few days ago when I was once again online shopping. I wasn’t really looking for anything in particular, just browsing, but each time I opened a new item I noticed these pop ups appearing. This is definitely a new feature of the Missguided website, as a loyal customer I know their site inside out, but this was the first time I had seen them use this nifty persuasion technique – Social Proof.Social proof is a phenomenon whereby people assume the actions of others in order to ensure or attempt to reflect the correct behaviour in certain situations. It is a type of conformity, we believe that others have interpreted a situation in a correct way and so we follow their lead. A notable study by Asch demonstrates this effect A group of 8, 1 participant and 7 confederates to the study, viewed 3 linesThey were asked to say which of the 3 lines matched the target line in sizeThis was a very unambiguous task, there was only one line which obviously matched the targetThe true participant answered last on all trials and the confederates consistently gave the wrong answer to the taskResults = 1/3rd of the time, participants conformed to the wrong answer of the confederatesThis study shows we base our ideas of what must be correct on what other people seem to be doing, it doesn’t matter what we think is true, it matters what everyone else thinks. So how does this fit into online shopping? Well, when I saw the jumpsuit I wasn’t sure if I liked it. It was a bit different, unlike most things I owned and I just all round wasn’t sure about it. However, the minute I was told ‘5 people are checking it out now’, ’26 purchases in the last 48 hours’ it was sold. Only after I received it today and realized that it is in fact not very nice at all did it sink in, I had been victim to Missguideds’ social proofing persuasion techniques. References: Gregory, S. (2009, March 4). Breaking news, analysis, politics, Blogs, news photos, video, tech reviews – TIME.Com. Retrieved November 17, 2016, from http://content.time.com/time/business/article/0,8599,1889081,00.htmlRetrieved November 17, 2016, from http://www.instantshift.com/2010/03/26/the-history-of-online-shopping-in-nutshell/Wolf, J. R., Arkes, H. R., & Muhanna, W. A. (2008). The power of touch: An examination of the effect of duration of physical contact on the valuation of objects. Judgment and Decision Making, 3, 476.

Well, when I saw the jumpsuit I wasn’t sure if I liked it. It was a bit different, unlike most things I owned and I just all round wasn’t sure about it. However, the minute I was told ‘5 people are checking it out now’, ’26 purchases in the last 48 hours’ it was sold. Only after I received it today and realized that it is in fact not very nice at all did it sink in, I had been victim to Missguideds’ social proofing persuasion techniques. References: Gregory, S. (2009, March 4). Breaking news, analysis, politics, Blogs, news photos, video, tech reviews – TIME.Com. Retrieved November 17, 2016, from http://content.time.com/time/business/article/0,8599,1889081,00.htmlRetrieved November 17, 2016, from http://www.instantshift.com/2010/03/26/the-history-of-online-shopping-in-nutshell/Wolf, J. R., Arkes, H. R., & Muhanna, W. A. (2008). The power of touch: An examination of the effect of duration of physical contact on the valuation of objects. Judgment and Decision Making, 3, 476.

How sampling can make you Famous

“Bad artists copy; great artists steal” – Pablo PicassoKanye West is many things; Rapper, clothes designer, self-proclaimed genius, future president, God etc. But perhaps his greatest work has come in his role as a producer, where he gained fame for his distinctive style of taking small sections of old soul songs by artists including Smokey Robinson, Marvin Gaye and Otis Redding, speeding them up and looping them to create a beat to rap over. This style of “stealing” classic artwork and reworking them into new expressions has been done by artists for centuries. A perfect example of Kanye’s sampling genius appears in his song Famous, from The Life of Pablo. In this song, he employees Rhianna to sing the hook originally from Nina Simone’s “Do What You Gotta Do” and loops sections of Sister Nancy’s “Bam Bam”. Combining these two hits with a now infamous line regarding Taylor Swift has seen Famous played over 160 million times on Spotify alone, more than “Do What You Gotta Do” and “Bam Bam” have combined, despite both tracks experiencing significant surges in the number of listens after the song was released.Even the music video for the song was a reinterpretation of a painting titled “Sleep”. Upon seeing Kanye’s remodelling the original artist, Vincent Desiderio, said his painting “had been sampled, or “spliced,” into a new format and taken to a brilliant and daring extreme!”

A perfect example of Kanye’s sampling genius appears in his song Famous, from The Life of Pablo. In this song, he employees Rhianna to sing the hook originally from Nina Simone’s “Do What You Gotta Do” and loops sections of Sister Nancy’s “Bam Bam”. Combining these two hits with a now infamous line regarding Taylor Swift has seen Famous played over 160 million times on Spotify alone, more than “Do What You Gotta Do” and “Bam Bam” have combined, despite both tracks experiencing significant surges in the number of listens after the song was released.Even the music video for the song was a reinterpretation of a painting titled “Sleep”. Upon seeing Kanye’s remodelling the original artist, Vincent Desiderio, said his painting “had been sampled, or “spliced,” into a new format and taken to a brilliant and daring extreme!” Vincent Desiderio’s “Sleep”

Vincent Desiderio’s “Sleep” Kanye West’s “Famous” The list of artists that have benefited from being featured on a Kanye song is extensive. From renowned stars such as Michael Jackson (P.Y.T. is sampled in Good Life), to film scores (the Imperial March from Star Wars provides the baseline for Hell of a Life), diversity of artists is impressive. But sampling doesn’t always work out well. Hungary’s most successful rock group Omega tried to sue Kanye for his use of their song Gyöngyhajú Lány at the end of New Slaves. Similar controversy can be seen in many different artistic fields. High street fashion retailer Zara is regularly accused of stealing designs from other brands or independent creators. Samsung currently owe Apple almost $120 million for various infringements on patents Apple owns, including swipe to unlock and autocorrect. It appears there is a fine line between artistic theft and illegal copying, and that line is incredibly subjective. Funnily enough, the quote that started this article has been adapted and reworded so many times it’s hard to know who said it first. The time line of the quotes has been traced, and offers up what essentially becomes a game of Chinese whispers spanning across centuries. The earliest quotation comes in 1892, where W. H. Davenport Adams says “that great poets imitate and improve, whereas small ones steal and spoil”. Since reworking’s of the general sentiment have been attributed to T. S. Elliot, Igor Stravinsky, Steve Jobs and Pablo Picasso. With that level of endorsement, its pretty clear how to advance in this world; Be a classy thief. References Kanye West- FamousPlaylist of songs Kanye has sampledDesiderio’s reaction to “Famous”Zara accused of stealing designsApple vs Samsung lawsuitTracing the origins of “Good Artists Copy; Great Artists Steal”

Kanye West’s “Famous” The list of artists that have benefited from being featured on a Kanye song is extensive. From renowned stars such as Michael Jackson (P.Y.T. is sampled in Good Life), to film scores (the Imperial March from Star Wars provides the baseline for Hell of a Life), diversity of artists is impressive. But sampling doesn’t always work out well. Hungary’s most successful rock group Omega tried to sue Kanye for his use of their song Gyöngyhajú Lány at the end of New Slaves. Similar controversy can be seen in many different artistic fields. High street fashion retailer Zara is regularly accused of stealing designs from other brands or independent creators. Samsung currently owe Apple almost $120 million for various infringements on patents Apple owns, including swipe to unlock and autocorrect. It appears there is a fine line between artistic theft and illegal copying, and that line is incredibly subjective. Funnily enough, the quote that started this article has been adapted and reworded so many times it’s hard to know who said it first. The time line of the quotes has been traced, and offers up what essentially becomes a game of Chinese whispers spanning across centuries. The earliest quotation comes in 1892, where W. H. Davenport Adams says “that great poets imitate and improve, whereas small ones steal and spoil”. Since reworking’s of the general sentiment have been attributed to T. S. Elliot, Igor Stravinsky, Steve Jobs and Pablo Picasso. With that level of endorsement, its pretty clear how to advance in this world; Be a classy thief. References Kanye West- FamousPlaylist of songs Kanye has sampledDesiderio’s reaction to “Famous”Zara accused of stealing designsApple vs Samsung lawsuitTracing the origins of “Good Artists Copy; Great Artists Steal”

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 113

- 114

- 115

- 116

- 117

- …

- 562

- Next Page »