Recent research out of the Arizona Canine Cognition Center suggests that “man’s best friend” are born ready to read body language and are capable of communicating and interacting with humans at a very young age with no formal training required.

Recent research out of the Arizona Canine Cognition Center suggests that “man’s best friend” are born ready to read body language and are capable of communicating and interacting with humans at a very young age with no formal training required.

Domestic dogs are born to socialize with humans because we bred them that way; the human-dog relationship goes back between 14,000–30,000 years ago and dogs have evolved alongside us. In fact, research even suggests that good are dogs at reading their owners’ emotions.

In this newest study study called “Early-emerging and highly heritable sensitivity to human communication in dogs” published in Current Biology found that two-month-old puppies can recognize when people are pointing at objects and will gaze at our faces when they’re spoken to – suggesting that dogs have an innate capacity to interact with us through body language.

Although individual relationships with people might influence that behavior, at least 40% of this ability comes from genetics alone, says lead researcher Emily Bray.

“These are quite high numbers, much the same as estimates of the heritability of intelligence in our own species. All these findings suggest that dogs are biologically prepared for communication with humans.”

The Study

Bray and colleagues have been working with Canine Companions, the largest United States service dog organization for people with physical disabilities, for over a decade, conducting research on how dogs think and solve problems.

For her latest study, Bray and colleagues studied 375 golden retriever and labrador trainee service puppies. At eight weeks old they are just old enough to be motivated by treats. Bray and colleagues put the puppies through three tests for human-dog communication:

To understand whether the pups’ early ability could be explained by their biology, all of them were of known heritage with a similar rearing history and pedigree, which helped build a statistical model assessing genetic versus environmental factors.

1) Classic Pointing Experiment

The researchers placed the young dogs between two overturned cups—one containing a treat—and pointing to the one with the treat. The animals understood the nonverbal gesture more than two-thirds of the time, approaching the performance of adult dogs. But they didn’t get any better over a dozen rounds, suggesting they were not learning the behavior.

2) Puppy Talk

In a second experiment, a researcher stood outside a large playpen and, for 30 seconds, engaged in the kind of high-pitched “puppy talk” familiar to almost anyone who has owned a dog: “Hey puppy, look at you! You’re such a good puppy.”

The animals spent an average of 6 seconds staring at the person. Such eye contact is rare among mammals and it’s an important foundation for social interaction with people.

3) Finding Food

In a final test, the researchers taught the puppies to find food in a plastic container, then sealed it with a lid. In contrast to adult dogs, which usually give up after a few seconds and look to humans for assistance, the pups rarely gazed at their scientist companions for help.

This suggested to the researchers that puppies seem to be sensitive to receiving information from humans and that they may not yet know that they can solicit help.

The post Puppies Read Body Language first appeared on Humintell.

What are some examples of things that trigger emotions? Getting stuck in traffic? Being hungry? Watching the news? How your partner squeezes the tube of toothpaste (yes, this is one of my pet peeves!)?

What are some examples of things that trigger emotions? Getting stuck in traffic? Being hungry? Watching the news? How your partner squeezes the tube of toothpaste (yes, this is one of my pet peeves!)?

In that last blog

In that last blog Contempt – Moral Superiority

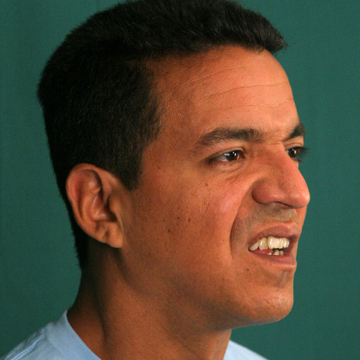

Contempt – Moral Superiority Disgust – Contamination

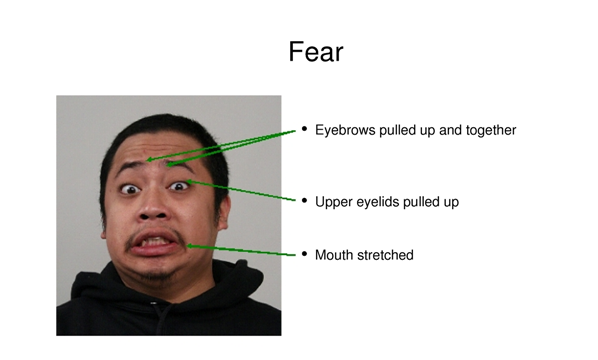

Disgust – Contamination Fear – Threat

Fear – Threat Happiness – Goal Attainment

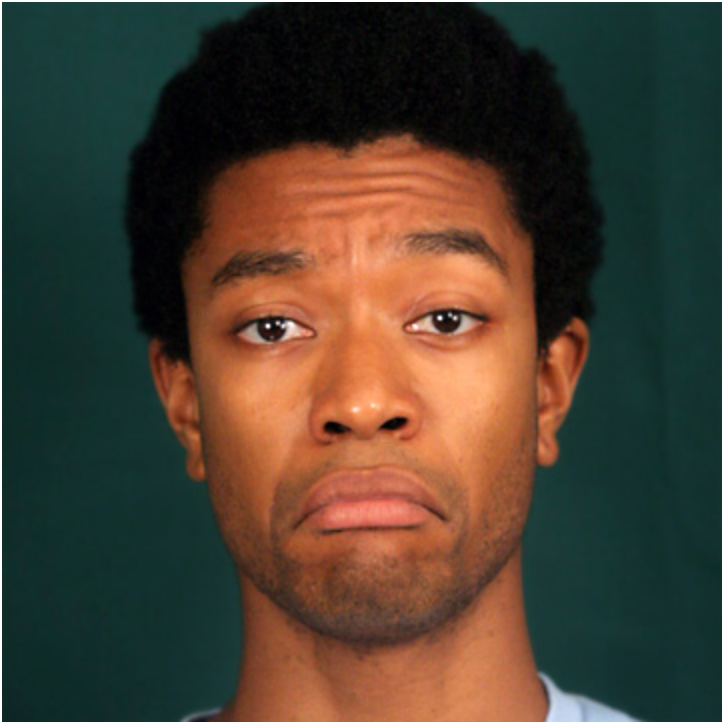

Happiness – Goal Attainment Sadness – Loss

Sadness – Loss Surprise – Novel Objects

Surprise – Novel Objects

What about the “emotion wheel”?

What about the “emotion wheel”?

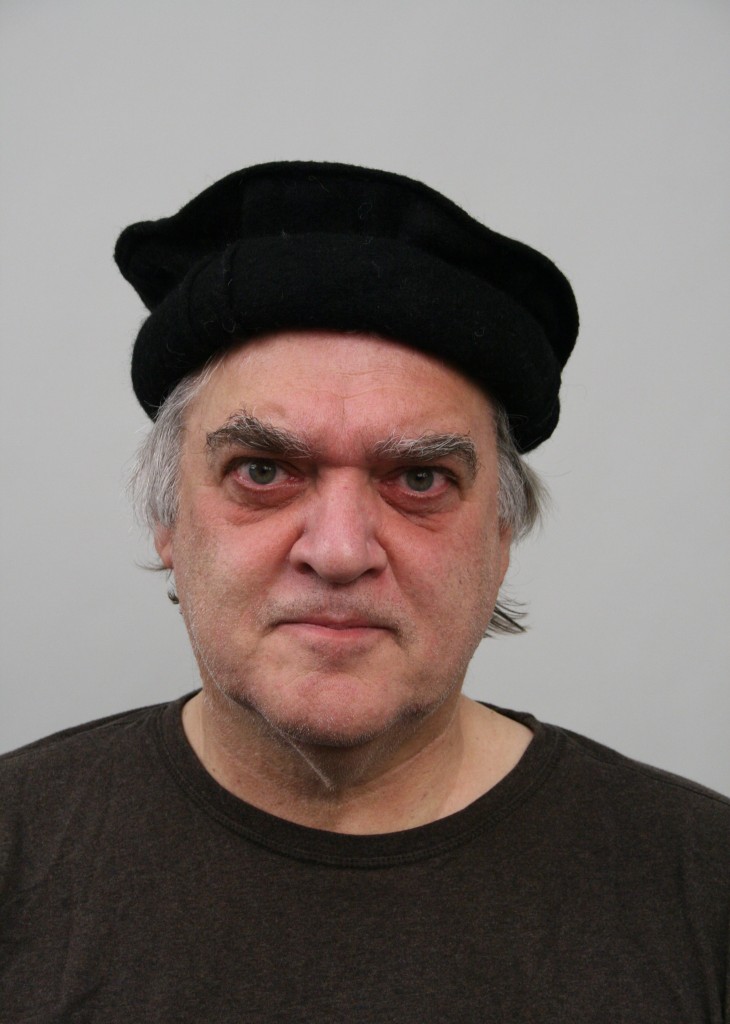

The anger family, for example includes low intensity anger words like frustrated and annoyed to high intensity words like enraged and hostile, and everything in between. And then there are all the other words that build upon anger, like jealousy. They’re all signaled by the universal angry

The anger family, for example includes low intensity anger words like frustrated and annoyed to high intensity words like enraged and hostile, and everything in between. And then there are all the other words that build upon anger, like jealousy. They’re all signaled by the universal angry