In one of our latest blogs, we wrote about the benefits of reading facial expressions of emotion. Those benefits all had to do with increasing our understanding of others, including gaining insights about their mental states, mindsets, personality, motivation, and intentions.

No doubt obtaining those insights and increasing our understanding of others is great, and we could sure use a LOT more of that in today’s world. But there’s also benefits of reading facial expressions of emotion to ourselves, and more importantly to our own personal effectiveness as well.

Improve Your Personal Effectiveness

Let’s explore how reading facial expressions of emotion in others can benefit one’s own personal effectiveness.

1. Allows us to self-reflect.

Seeing that others may be angry, sad, disgusted, or even happy allows us to think about how we may be contributing to those emotions or how we may be coming off to others to produce their emotional reactions.

When we interpret the reasons why others are emotional, we should consider how we may have contributed to those emotions, which may come from either our words or actions. Even if we think we are being calm, logical, rational, or objective, the way we say things may not be so. For the most part, we are not conscious of our own demeanor and how we may be coming off to others, and that may be a reason why others are emotional.

Being aware of and reading other’s emotional expressions allows us to better monitor ourselves and our own reactions, demeanor, and style; doing so helps us be more effective because we are in control of our responses, not vice versa.

But at the same time, let’s also remember that there’s a danger in interpreting other’s emotional states because of oneself because that may or may not be true. The danger in thinking that way occurs when one consistently thinks that one is the source of other’s emotions. That kind of thinking is a version of what I call the “me theory.”

Another version of the “me theory” says that “I know why the other person is emotional because if I were them I would feel that way.” This also may or may not be true. The only person who really knows why they are emotional is that person and if knowing it is important to you, then you need to be able to get the person to talk about it.

Whenever we train people to read other’s facial expressions of emotion, we always caution in these possibly erroneous interpretations. Instead, what I am saying here is that reading other’s facial expressions of emotion give us a chance to self-reflect about ourselves so that we can be more effective, regardless of whether we are the source of the other person’s emotions.

2. Allows us to be more strategic.

When we observe other’s emotions, we can stop and think about our where we are in the interaction and consider how we can navigate moving forward given what we just observed so that can be on track and achieve our goals. After all, there’s a reason why someone becomes emotional, and those reasons could include either the content of the conversation or the process of having the conversation.

Regardless of which is the source of the other’s emotion, if we think strategically, we can consider ways in which we can leverage those emotions to achieve our goals (of course in ethical ways).

3. Can lead to growth in one’s interactive skills.

In everyday life, most people really don’t tune into other’s emotional reactions, especially the many nuances of expressions that occur in the ebb and flow of any interaction. Instead, facial expressions and other nonverbal behavior are often just background behavior that occurs above and beyond words, and we often focus on words to the exclusion of the nonverbals.

But if we are more in tune with what’s going on in other people’s emotional reactions, as well as all other kinds of nonverbal behavior, we will be a better listener AND observer, which are beneficial skills that can carry over in any interaction, whether professional or personal.

4. Benefits our relationships.

Reading others’ facial expressions of emotion can be a force multiplier. It allows us to understand others on an emotional basis, deepen our conversations with others, and be the basis for increasing empathy and sharing emotions.

Understanding, acknowledging, and sharing emotions are all foundations for the development and maintenance of rapport and trust. All these indirectly improve one’s own personal effectiveness by enrichening our relationships with those with whom we live, work and play, and better relationships help us be more effective.

Some Pitfalls of Reading Facial Expressions

But there’s some pitfalls, too, and we mention them here so that we can all be on top of them and don’t let them distract us from being effective.

For one, emotions are contagious. Research on the concept of emotion contagion (especially by the excellent scholar Elaine Hatfield) and on mirror neurons inform us that reading other’s emotional expressions may lead to the triggering of emotions in ourselves. In fact, there may be unconscious and automatic processes at work when we read other’s emotional expressions to do just that.

Becoming emotional can detract us from staying on track, being strategic, and being effective in order to achieve our goals. Thus, when we observe other’s emotional reactions, we also have to recognize our own emotional triggers and sensations that occur when we are emotional so we don’t get distracted or allow those emotions to overwhelm us. Reading facial expressions of emotion in any interaction that is meaningful requires, at least to some degree, that we do so with some clinical detachment. Clinical detachment takes time and effort, especially when conversations involve something that is meaningful for yourself and occur with people who are meaningful to you.

Reading other’s facial expressions of emotion can be perceived as intrusive or rude, especially if one is perceived as staring. Performing this skill well requires one to be practiced well enough to do it naturally in the flow of conversation.

Finally, reading others facial expressions of emotion can be distracting. Because facial behavior is dynamic, paying attention to faces can be seductive and one can easily get sucked in to watching and reading faces and get off track from the purpose of the interaction. Reading others’ facial expressions of emotion should be a means to an end, a hopefully mutually positive and beneficial end, but not an end in itself.

Despite these pitfalls, reading others’ facial expressions of emotion is an amazing skill that not only has benefits for our insights about others; it also can make wonderful contributions to insights about ourselves and the process by which we interact with others.

Engaging in thoughtful and objective interpretation and evaluation of others’ emotions can improve our critical thinking skills. Clearly, improving our own personal effectives and leveraging insights about others as well as ourselves can have direct and indirect benefits to our own personal effectiveness, if and when applied wisely.

For those of you have learned the basics of reading facial expressions of emotion with one of our online courses, challenge yourself to become even more skilled in reading them with other, more advanced courses. For those of you have haven’t yet experienced learning to read facial expressions of emotion with one of our introductory courses, give it a shot! Now’s the time, for all the reasons above.

If you learn to read facial expressions of emotion and incorporate that skill into your professional practices, interviews, negotiations, sales, and the like, it will be a force multiplier like you’ve never witnessed.

The post 4 Personal Benefits of Reading Facial Expressions of Emotion first appeared on Humintell.

Studies have shown that infants are sensitive to emotions expressed through facial expressions since their first year of birth. In fact, a study published in PLOS ONE,

Studies have shown that infants are sensitive to emotions expressed through facial expressions since their first year of birth. In fact, a study published in PLOS ONE,

Of all these signals, facial expressions of emotion are very, very special, because emotions are special types of psychological phenomena. As we’ve been discussing in our past few blogs, emotions are reactions to events that are meaningful for us.

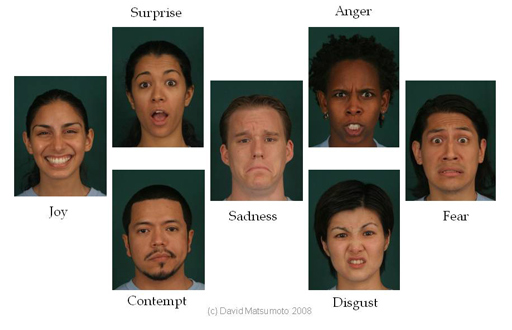

Of all these signals, facial expressions of emotion are very, very special, because emotions are special types of psychological phenomena. As we’ve been discussing in our past few blogs, emotions are reactions to events that are meaningful for us.  Facial expressions are also special because they can signal different, discrete emotions (otherwise known as the

Facial expressions are also special because they can signal different, discrete emotions (otherwise known as the

Thus, reading each of the universal facial expressions of emotion is so important because when we read faces, we are actually reading the mind processing and evaluating stimuli. And when we see a specific, discrete emotion, we know how they evaluated something. We know the direction of what people are thinking, and equally important, we know what their bodies are primed to do doing before they do. Think about how important this is for people in harm’s way.

Thus, reading each of the universal facial expressions of emotion is so important because when we read faces, we are actually reading the mind processing and evaluating stimuli. And when we see a specific, discrete emotion, we know how they evaluated something. We know the direction of what people are thinking, and equally important, we know what their bodies are primed to do doing before they do. Think about how important this is for people in harm’s way. There are additional benefits to being interested in reading facial expressions of emotion, too. Doing so shows interest in others by paying attention.

There are additional benefits to being interested in reading facial expressions of emotion, too. Doing so shows interest in others by paying attention.