Marco Germani is our guest blogger for this month’s “Influencers from Around the World” post. Marco lives in Italy, just outside of Rome. He’s not only been a guest blogger in the past, he wrote a book on influence in Italian. Marco is married and has two young boys. He gets real world influence application in his various business pursuits. Readers have always enjoyed Marco’s perspective on influence and I’m sure that will be the case this month. Brian Ahearn, CMCT® Chief Influence Officer influencePEOPLE Helping You Learn to Hear “Yes”.Italians and the Principle of LikingI recently read about a survey conducted by Citibank, a corporation with employees across the globe. The object was to identify how the different persuasion principles would apply to different cultures around the world. The question asked of employees was: If someone within your organization came to ask you for help on a project, and this project would take you away from your own duties, under what circumstances you would be mostly obligated to help?The results displayed that in the U.S., the principle mostly taken into account to answer this question was reciprocity. What has this person done for me? Do I feel obliged to render him a favor? That would determine whether the help is granted or not.In Hong Kong, the most important principle was authority: is this person connected to my small group and in particular, is he a senior member of this group? In Germany, authority was considered but under a different light: according to the rules and regulations, am I supposed to say yes? In this case, I am obliged. Finally, in Italy, yet another persuasion principle was mainly taken into account: the one of liking. Is this person connected to my friends? I am loyal to my friends so, therefore, I must help him or her.Being an Italian I can confirm this is true most of the time. I then started to think about the reason this principle is so important for Italians and I came up with my own theory. It goes back to my country’s history. Contrary to what happened in other European countries, like France and Germany, Italy started to exist as a single centralized unit only quite recently (250 years ago, which for Europe is a really short time). For thousands of years, the regions eventually forming Italy existed as isolated kingdoms (Kingdom of Naples, Kingdom of the two Sicilies, etc.) and often fought bitterly against each other.When Italy became a nation it was hard, for a central government, back then based in Piedmont in northern Italy, to maintain control while being politically and physically present in the whole country. This was especially true in southern regions like Calabria or Sicilia. The formation of small clans of people, which eventually led to the creation of the most (unfortunately) famous criminal organization in the world, the Mafia, became a necessity of survival. Where the hand of the government couldn’t reach, there you had a small group of “friends” ready to kill for each other in order to keep order and peace and fight against the “bad guys.” If you wanted protection, you must become their friend too. If not, bad things could happen to you. Assuming this theory has some part of truth, it must be eradicated in our DNA a sense of loyalty to our group of friends, not anymore for survival, but to have some kind of advantage in our daily lives, according also to the principle of reciprocity.This can be observed also when two or more Italians meet abroad. We tend to establish as soon as possible a sort of connection, because we know that we could, as a small team (or clan) be more effective in overcoming problems and finding solutions. Of course this happens without any criminal or illegal intention nowadays. On the other hand, in a business setting, this is a universal rule, which transcends cultures: always try to build a relationship with your customer or business partner before talking shop. With us Italians, it is even more important and it is an aspect which should never be underestimated by any serious negotiator or influencer.

Brian Ahearn, CMCT® Chief Influence Officer influencePEOPLE Helping You Learn to Hear “Yes”.Italians and the Principle of LikingI recently read about a survey conducted by Citibank, a corporation with employees across the globe. The object was to identify how the different persuasion principles would apply to different cultures around the world. The question asked of employees was: If someone within your organization came to ask you for help on a project, and this project would take you away from your own duties, under what circumstances you would be mostly obligated to help?The results displayed that in the U.S., the principle mostly taken into account to answer this question was reciprocity. What has this person done for me? Do I feel obliged to render him a favor? That would determine whether the help is granted or not.In Hong Kong, the most important principle was authority: is this person connected to my small group and in particular, is he a senior member of this group? In Germany, authority was considered but under a different light: according to the rules and regulations, am I supposed to say yes? In this case, I am obliged. Finally, in Italy, yet another persuasion principle was mainly taken into account: the one of liking. Is this person connected to my friends? I am loyal to my friends so, therefore, I must help him or her.Being an Italian I can confirm this is true most of the time. I then started to think about the reason this principle is so important for Italians and I came up with my own theory. It goes back to my country’s history. Contrary to what happened in other European countries, like France and Germany, Italy started to exist as a single centralized unit only quite recently (250 years ago, which for Europe is a really short time). For thousands of years, the regions eventually forming Italy existed as isolated kingdoms (Kingdom of Naples, Kingdom of the two Sicilies, etc.) and often fought bitterly against each other.When Italy became a nation it was hard, for a central government, back then based in Piedmont in northern Italy, to maintain control while being politically and physically present in the whole country. This was especially true in southern regions like Calabria or Sicilia. The formation of small clans of people, which eventually led to the creation of the most (unfortunately) famous criminal organization in the world, the Mafia, became a necessity of survival. Where the hand of the government couldn’t reach, there you had a small group of “friends” ready to kill for each other in order to keep order and peace and fight against the “bad guys.” If you wanted protection, you must become their friend too. If not, bad things could happen to you. Assuming this theory has some part of truth, it must be eradicated in our DNA a sense of loyalty to our group of friends, not anymore for survival, but to have some kind of advantage in our daily lives, according also to the principle of reciprocity.This can be observed also when two or more Italians meet abroad. We tend to establish as soon as possible a sort of connection, because we know that we could, as a small team (or clan) be more effective in overcoming problems and finding solutions. Of course this happens without any criminal or illegal intention nowadays. On the other hand, in a business setting, this is a universal rule, which transcends cultures: always try to build a relationship with your customer or business partner before talking shop. With us Italians, it is even more important and it is an aspect which should never be underestimated by any serious negotiator or influencer. Marco

Marco

The Sleep-Deprived Brain Can Mistake Friends for Foes

Photo courtesy of MeditationMusic.net

If you can’t tell a smile from a scowl, you’re probably not getting enough sleep.

A new UC Berkeley study shows that sleep deprivation dulls our ability to accurately read facial expressions. This deficit can have serious consequences, such as not noticing that a child is sick or in pain, or that a potential mugger or violent predator is approaching.

“Recognizing the emotional expressions of someone else changes everything about whether or not you decide to interact with them, and in return, whether they interact with you,” said study senior author Matthew Walker, a professor of psychology and neuroscience at UC Berkeley. The findings were published today in the Journal of Neuroscience.

“These findings are especially worrying considering that two-thirds of people in the developed nations fail to get sufficient sleep,” Walker added.

Indeed, the results do not bode well for countless sleep-starved groups, said study lead author Andrea Goldstein-Piekarski, a postdoctoral fellow at Stanford University, who started the study as a Ph.D. student at UC Berkeley.

“Consider the implications for students pulling all-nighters, emergency-room medical staff, military fighters in war zones and police officers on graveyard shifts,” she said.

For the experiment, 18 healthy young adults viewed 70 facial expressions that ranged from friendly to threatening, once after a full night of sleep, and once after 24 hours of being awake. Researchers scanned participants’ brains and measured their heart rates as they looked at the series of visages.

Brain scans as they carried out these tasks – generated through functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) – revealed that the sleep-deprived brains could not distinguish between threatening and friendly faces, specifically in the emotion-sensing regions of the brain’s anterior insula and anterior cingulate cortex.

Additionally, the heart rates of sleep-deprived study participants did not respond normally to threatening or friendly facial expressions. Moreover, researchers found a disconnection in the neural link between the brain and heart that typically enables the body to sense distress signals.

“Sleep deprivation appears to dislocate the body from the brain,” said Walker. “You can’t follow your heart.”

As a consequence, study participants interpreted more faces, even the friendly or neutral ones, as threatening when sleep-deprived.

“They failed our emotional Rorschach test,” Walker said. “Insufficient sleep removes the rose tint to our emotional world, causing an overestimation of threat. This may explain why people who report getting too little sleep are less social and more lonely.”

On a more positive note, researchers recorded the electrical brain activity of the participants during their full night of sleep, and found that their quality of Rapid Eye Movement (REM) or dream sleep correlated with their ability to accurately read facial expressions. Previous research by Walker has found that REM sleep serves to reduce stress neurochemicals and soften painful memories.

“The better the quality of dream sleep, the more accurate the brain and body was at differentiating between facial expressions,” Walker said. “Dream sleep appears to reset the magnetic north of our emotional compass. This study provides yet more proof of our essential need for sleep.”

Training Boys to Recognize Another’s Fear Reduces Violent Crime

Written by Jessica Hamzelou for New Scientist Magazine

Written by Jessica Hamzelou for New Scientist Magazine

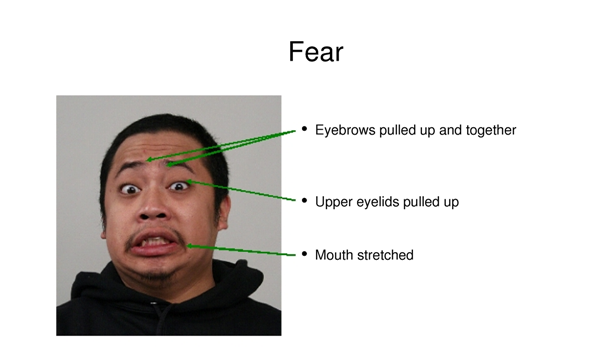

Wide eyes and mouth agape – you might think a fearful face is easy to recognize. That doesn’t seem to be the case for people who repeatedly commit antisocial offences. For the first time, training offenders to better read facial expressions has reduced violent crime.

The computer-based training – which only requires one person and a laptop to administer – is a promising new lead for managing antisocial behavior.

Under UK law, such behavior is defined as that which causes harassment, alarm or distress to another person, and includes violent crime, theft and criminal damage. People that repeatedly engage in this kind of behavior, with scant regard for those they hurt, are described as having antisocial personality disorder by the American Psychological Association.

“People tend to think that children who show antisocial behaviors are just criminals,” says Stephane de Brito at the University of Birmingham, UK. “But if these behaviors persist, they are at an increased risk of developing so many problems, such as psychotic illness, depression and substance abuse.”

In an effort to avoid this, children can be monitored and receive training from youth offender services. Other approaches target schools with anti-bullying programs, or offer support to parents. “There’s a lot done, and a lot of money is invested, but the programs are not having as much success as one would hope for,” says Stephanie van Goozen, a biological psychologist at Cardiff University in Wales.

Reading Faces

Van Goozen and her colleagues decided to try a different approach. The team turned to the psychological theory that people who harm others may do so because they can’t tell that their victim is distressed. Research has shown that both adult psychopaths and children diagnosed with “conduct disorder”, which is associated with antisocial behavior, struggle to recognize fear in the faces of other people.

When these children engage in behavior that is unpleasant or causes pain, they can’t tell that that the other person is suffering, so feel no need to correct their behavior, says van Goozen.

To find out if learning to recognize emotions would help these children to rein in their behavior, van Goozen’s team used a computer-based program that teaches people to recognize facial expressions. The system was originally developed by a team in the US to help people with brain injuries relearn the rules of social interactions.

They trained half of a group of 50 boys who had been convicted of a crime to recognize happiness, sadness, fear and anger in facial expressions. Each participant was aged between 12 and 18, and completed a total of between 7 and 9 hours of training over two or three sessions. “Gradually you teach people to pay attention to the right signals in the face, such as the eyes and the mouth – the things that tell you how intensely people feel,” says van Goozen. Her team also made a note of the crimes that all the boys had committed in the past, and those that were committed in the six months following training.

The team found that boys who received training significantly improved in their ability to recognize fear, anger and sadness in others’ faces, while those who had no training did not. Moreover, while all of the participants committed fewer offences than in the six months before the training – probably because they were closely monitored – in those who’d had training the crimes were significantly less violent and severe, and tended to involve theft rather than physical aggression. It is the first time that emotion training has been found to affect real-world crime.

Costly Crime

“It’s an important study,” says Richard Rowe, a psychologist who specializes in antisocial behavior at Sheffield University in the UK. While it is too early to make policy decisions based on one relatively small study, he says the findings represent an exciting new lead.

One advantage is the technique’s low cost. Antisocial behavior is expensive – by the age of 28, those who have engaged in it persistently from age 10 can end up costing society around 10 times more than those without a similar history, due to lost productivity as well as education and criminal justice system costs.

Money is currently spent on initiatives like support programs for the parents of offenders, but these tend to work best in families with the least problems. “My issue is that these programs might work in some kids but they don’t work in all kids, and they particularly don’t work in kids that need it most,” says van Goozen.

Van Goozen’s technique seems promising and low-cost, says Rowe. “All you need is one person and a laptop,” says van Goozen, who now plans to test the program in more young people, as well as children as young as 4 who might be at risk of developing antisocial behavior, because they have been abused, for example. She thinks it could work in adults too, given the success of similar training programs aimed at adults with brain injury in the US.

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 208

- 209

- 210

- 211

- 212

- …

- 562

- Next Page »