Courtesy of StockVault

People tend to measure dishonesty by a person’s physical tells such as fidgeting, breathing rate, etc. Often times these tells coupled with the baseline of the individual and intuition leads us to be correct in our analysis when it is someone we know well. However, these techniques including measuring blood pressure and pulse as in a polygraph, are not admissible as hard evidence of deception in any legal form.

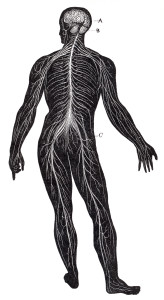

It is for a good reason that these signs of anxiety are not reliable indicators of a person’s honesty. They can be a representation of nervousness or just how a person normally behaves. Science has long tried to accurately map out lies from truths using technology and with the exponential growth of technology today, researchers can now delve into our brains.

Today researchers studying the brain and deception use a full body scanner that employs functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) technology to determine whether someone is fibbing by tracing blood flow to certain areas of the brain, which indicates changes in neuronal activity at the synapses (gaps between the neurons). “If you’re using fMRI, the scanner is detecting a change in the magnetic properties in the blood,“ says Sean Spence, a professor of general adult psychiatry at the University of Sheffield in England.

Scientific American notes in their article about this research that hemoglobin molecules in red blood cells exhibit different magnetic properties depending on the amount of oxygen they contain. The most active brain regions use—and thereby contain—the most oxygen.

Spence goes on to note, “When you know the answer to a question, the answer is automatic; but to avoid telling me the true answer requires something more.“ Polygraph, or lie detector, tests are the most well-known method of discerning fact from fiction, but researchers say they are not reliable because they measure anxiety based on a subject’s pulse or breathing rate, which can easily be misread. “They’re not detecting deception but rather the anxiety of being…[accused of deception],“ Spence says. “It’s known that psychopaths have a reduced level of anxiety,“ that would allow them to fool a polygraph. The fMRI, he says, images the actual processes involved in deception.

The researchers had a unique opportunity to study a woman convicted of poisoning a child in her care. This provided a stage for Spence and his colleagues to extend their, which until then had only been conducted on young, healthy university students as many studies of this sort do.

The team used an fMRI on Susan Hamilton of Edinburgh, Scotland, who was convicted of poisoning with salt a girl diagnosed with a terminal metabolic condition. Hamilton, who was in charge of feeding the child via a feeding tube that led directly into her stomach, was arrested after the girl was admitted to the hospital with massive blood sodium levels. The police testified that a syringe full of salt was found in Hamilton’s kitchen, but she denies any knowledge of it. The woman was released from prison last year and has continued to search for ways to publicly prove her professed innocence.

The researchers scanned Hamilton four times; during each scan they grilled her about the poisoning. With the fMRI, Spence was able to see that she activated extensive regions of her frontal brain lobes and also took significantly longer to respond when agreeing with the cops’ account. The results did not prove her innocent, Spence says, but suggested that her brain was responding as if she were innocent.

Spence and his team acknowledge that the results might have been more accurate if he had first done a baseline study that included asking her more general questions unrelated to the charges. Unfortunately, TV is show biz and his time with her was limited.

“Being able to study this lady pointed out problems with the technique,“ the researchers note, “There are a number of control studies we want to do.“

As of January 2014 Affectiva, a facial expression analysis firm renewed its multi-million, multi-year agreement with Millward Brown. Millward Brown will use Affectiva’s technology in their automated facial coding software that they implement for their Link Clients, which allows them to validate the performance of their advertising and identify strengths and weaknesses.

As of January 2014 Affectiva, a facial expression analysis firm renewed its multi-million, multi-year agreement with Millward Brown. Millward Brown will use Affectiva’s technology in their automated facial coding software that they implement for their Link Clients, which allows them to validate the performance of their advertising and identify strengths and weaknesses. I had in interesting Facebook exchange not long ago. Someone posted a picture of an attractive young woman wearing a t-shirt that had the following message on the front, “To be old and wise you must first be young and stupid.” To be honest I didn’t pay attention to the rest of the post, which read, “Reinvent yourself with enhanced awareness, renew yourself with enhanced tolerance and regenerate yourself with enhanced wisdom.”Focused on the picture and the saying imprinted on it I light-heartedly commented, “But if you’re too stupid when you’re young you may not live long enough to become old and wise. : ) ”My Facebook friend replied, “@Brian: You mean ONLY stupid people die young?? Just to refocus your observation on the quote which is my thought – it is not on the t-shirt.”I replied one last time to let him know I didn’t think only stupid people die young. Of course, the more stupid things you do, the more risk you run of harming yourself, but even people who make good decisions experience bad things. This week’s post isn’t about Facebook or the stupid things young people sometimes do. What stood out to me after the exchange was the following communication problem that’s all too common – the message was incongruent.You see, the picture of the attractive lady stood out and in my mind the message on her t-shirt had nothing to do with my friend’s quote, which was what he really wanted to convey to readers. Again, his quote was, “Reinvent yourself with enhanced awareness, renew yourself with enhanced tolerance and regenerate yourself with enhanced wisdom.” If there was a connection, then how many others missed it too?When you’re trying to communicate with someone, perhaps even trying to persuade him or her, you’d better be sure every part of your message is congruent. For example, if I conduct a sales training session for business professionals I’d be foolish to not dress in a suit and tie or sports coat at a minimum. If I went to a training session dressed as I do on the weekends my appearance will detract from my message. People have expectations about how a sales trainer will dress just like you probably have ideas about how a minister should look at a wedding or a lawyer in a courtroom. When there’s a mismatch people can lose focus and the last thing you want is someone focused on how you look rather than your message.We also have expectations for the environments we find ourselves in. We don’t act the same in church as we do at work, a bar, or in a college classroom. We conduct ourselves differently in each place and acting like you’re talking in church to a room full of college students will lose them faster than they can update Twitter.When you want to communicate a message make sure everything has a purpose and that every part of the message builds to your main point. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve heard people say after a training session, “It was pretty good but he kept going off on these tangents that had nothing to do with the workshop.” If you have stories to share, make sure they add to the message and don’t detract from it.Practice helps and perfect practice makes perfect. Do you ever ask someone for feedback on a presentation before you give it? Running through your presentation with another, as you would if your audience were right there, will help you in multiple ways. One big way is to make sure the person sees how everything ties together. If you have to stop and make the connections for them then you might want to rethink your approach.The same can be said of writing. Have someone proof read your articles and blogFree webinar! Would you like to learn more about influence from the experts? Check out the Cialdini “Influence” Series featuring Cialdini Method Certified Trainers from around the world. posts. Have them challenge you and if something doesn’t make sense, ask yourself if there’s a better way to convey the message. Again, if you have to take extra time to explain what you mean then that should be a signal that other readers might not get your point either.Communicating a message is like traveling to a destination. Usually the shortest, most direct route is best. If you want to get there in a hurry then limit your excursions and make sure everything is working together like a well-oiled machine. The extra time and effort will be worth it when people go, “Ah, I get it.”

I had in interesting Facebook exchange not long ago. Someone posted a picture of an attractive young woman wearing a t-shirt that had the following message on the front, “To be old and wise you must first be young and stupid.” To be honest I didn’t pay attention to the rest of the post, which read, “Reinvent yourself with enhanced awareness, renew yourself with enhanced tolerance and regenerate yourself with enhanced wisdom.”Focused on the picture and the saying imprinted on it I light-heartedly commented, “But if you’re too stupid when you’re young you may not live long enough to become old and wise. : ) ”My Facebook friend replied, “@Brian: You mean ONLY stupid people die young?? Just to refocus your observation on the quote which is my thought – it is not on the t-shirt.”I replied one last time to let him know I didn’t think only stupid people die young. Of course, the more stupid things you do, the more risk you run of harming yourself, but even people who make good decisions experience bad things. This week’s post isn’t about Facebook or the stupid things young people sometimes do. What stood out to me after the exchange was the following communication problem that’s all too common – the message was incongruent.You see, the picture of the attractive lady stood out and in my mind the message on her t-shirt had nothing to do with my friend’s quote, which was what he really wanted to convey to readers. Again, his quote was, “Reinvent yourself with enhanced awareness, renew yourself with enhanced tolerance and regenerate yourself with enhanced wisdom.” If there was a connection, then how many others missed it too?When you’re trying to communicate with someone, perhaps even trying to persuade him or her, you’d better be sure every part of your message is congruent. For example, if I conduct a sales training session for business professionals I’d be foolish to not dress in a suit and tie or sports coat at a minimum. If I went to a training session dressed as I do on the weekends my appearance will detract from my message. People have expectations about how a sales trainer will dress just like you probably have ideas about how a minister should look at a wedding or a lawyer in a courtroom. When there’s a mismatch people can lose focus and the last thing you want is someone focused on how you look rather than your message.We also have expectations for the environments we find ourselves in. We don’t act the same in church as we do at work, a bar, or in a college classroom. We conduct ourselves differently in each place and acting like you’re talking in church to a room full of college students will lose them faster than they can update Twitter.When you want to communicate a message make sure everything has a purpose and that every part of the message builds to your main point. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve heard people say after a training session, “It was pretty good but he kept going off on these tangents that had nothing to do with the workshop.” If you have stories to share, make sure they add to the message and don’t detract from it.Practice helps and perfect practice makes perfect. Do you ever ask someone for feedback on a presentation before you give it? Running through your presentation with another, as you would if your audience were right there, will help you in multiple ways. One big way is to make sure the person sees how everything ties together. If you have to stop and make the connections for them then you might want to rethink your approach.The same can be said of writing. Have someone proof read your articles and blogFree webinar! Would you like to learn more about influence from the experts? Check out the Cialdini “Influence” Series featuring Cialdini Method Certified Trainers from around the world. posts. Have them challenge you and if something doesn’t make sense, ask yourself if there’s a better way to convey the message. Again, if you have to take extra time to explain what you mean then that should be a signal that other readers might not get your point either.Communicating a message is like traveling to a destination. Usually the shortest, most direct route is best. If you want to get there in a hurry then limit your excursions and make sure everything is working together like a well-oiled machine. The extra time and effort will be worth it when people go, “Ah, I get it.” Brian Ahearn, CMCT® Chief Influence Officer influencePEOPLE Helping You Learn to Hear “Yes”. Free webinar! Would you like to learn more about influence from the experts? Check out the Cialdini “Influence” Series featuring Cialdini Method Certified Trainers from around the world.

Brian Ahearn, CMCT® Chief Influence Officer influencePEOPLE Helping You Learn to Hear “Yes”. Free webinar! Would you like to learn more about influence from the experts? Check out the Cialdini “Influence” Series featuring Cialdini Method Certified Trainers from around the world.