Any parent of young children know that raising kids can be a bit messy, especially when they’re infants. In addition to plenty of kisses, there’s always drool to be wiped, and slobbery feedings.

Recent research has shown that exposure to family members’ saliva, what is known in the academic world as “saliva sharing”, plays a crucial role in how we make sense of the world around us. It helps shape our discernment of social relationships, starting from our first months of life.

The study entitled “Early concepts of intimacy: young humans use saliva sharing to infer close relationships” was led by Ashley Thomas and recently published in the journal Science.

At MIT, Thomas studies how infants recognize different types of social relationships and how they learn about their specific social worlds, how they place themselves into relationships and into larger social groups.

Saliva Sharing

As reported in MIT News, In human societies, people typically distinguish between “thick” and “thin” relationships.

Thick relationships, usually found between family members, feature strong levels of attachment, obligation, and mutual responsiveness. Anthropologists have also observed that people in thick relationships are more willing to share bodily fluids such as saliva.

“That inspired both the question of whether infants distinguish between those types of relationships, and whether saliva sharing might be a really good cue they could use to recognize them,” Thomas says.

To study those questions, the researchers observed toddlers (16.5 to 18.5 months) and babies (8.5 to 10

months) as they watched interactions between human actors and puppets. In the first set of experiments, a puppet shared an orange with one actor, then tossed a ball back and forth with a different actor.

After the children watched these initial interactions, the researchers observed the children’s reactions when the puppet showed distress while sitting between the two actors. Based on an earlier study of nonhuman primates, the researchers hypothesized that babies would look first at the person whom they expected to help. That study showed that when baby monkeys cry, other members of the troop look to the baby’s parents, as if expecting them to step in.

The MIT team found that the children were more likely to look toward the actor who had shared food with the puppet, not the one who had shared a toy, when the puppet was in distress.

In future work, the researchers hope to perform similar studies with infants in cultures that have different types of family structures. In adult subjects, they plan to use functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to study what parts of the brain are involved in making saliva-based assessments about social relationships.

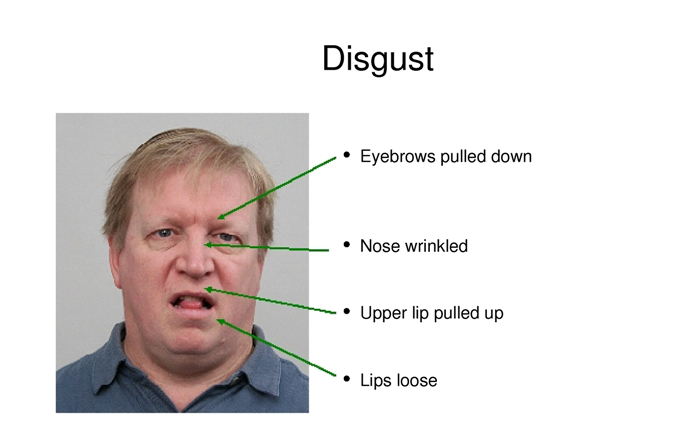

Related to Disgust

In a commentary published alongside this new study reported by BT Times, Christine Fawcett of Uppsala University in Sweden notes that the findings not only bring to light what young children understand about the social structures around them, but also raise further questions about how children acquire these expectations and how universal they may be.

In a commentary published alongside this new study reported by BT Times, Christine Fawcett of Uppsala University in Sweden notes that the findings not only bring to light what young children understand about the social structures around them, but also raise further questions about how children acquire these expectations and how universal they may be.

She points out that exchanging saliva with a stranger might make individuals feel disgusted, possibly as a method to protect themselves from contamination or disease, but that people will willingly do so with those close to them, even their pets.

According to Fawcett, there may be an evolutionary pressure to suppress disgust with body substances in order to aid in the care of babies, and infants’ experience with this type of caretaking may then lead to a learned expectation that such behavior is connected with closeness.

Various volunteers took part in the series of experiments, but as the study progressed, the researchers recruited a more geographically, ethnically, and economically diverse population. However, all of the participants were from the U.S.

While saliva sharing may be an universal cue, Thomas pointed out that saliva norms and who is considered family vary around the world – and so may what seeing a saliva sharing connection imply.

The post Babies use ‘Saliva Sharing’ to Infer Close Relationships first appeared on Humintell.