How important is language in communication really?

How important is language in communication really?

This may seem like a silly question, but in such a large and diverse world, the myriad of languages present particular challenges to jetsetters and tourists of all sorts. No matter how many languages you know, the intrepid world traveler can never be fluent in the language of every nation. What can we do to better communicate if we don’t speak the same language?

The good news is that, according to Humintell’s own Dr. David Matsumoto, language is not actually the most important factor in cross cultural communication. Instead, a few simple phrases, combined with a focus on positive nonverbal communication can go a long way towards promoting communication without fluency.

As Dr. Matsumoto says in an interview with Psychology Today: “If you are good at non-verbal communication then you can go anywhere without knowing the language and you will get along.”

He elaborates on the fact that language is really just one part of a given interaction. In every conversation, our body language, facial expression, and gestures convey a wealth of information concerning our intentions and emotions.

In fact, sometimes linguistic fluency, if divorced from nonverbal behavior, can lead to conflict and misunderstanding. “Verbal language by itself only communicates a certain amount of content,” Dr. Matsumoto explains, “People can be saying the content they want to communicate, but just not come across correctly.”

Many of us who learned foreign language in school focused on memorizing verb tables, practicing vocabulary, and translating written documents. However, that leaves out the important aspect of body language, which can vary between cultures. Instead, Dr. Matsumoto points out that “data shows that language classes that incorporate non-verbal communication and culture in their curricula fair better.”

So, we’ve established the importance of non-verbal communication, but exactly how should this be practiced?

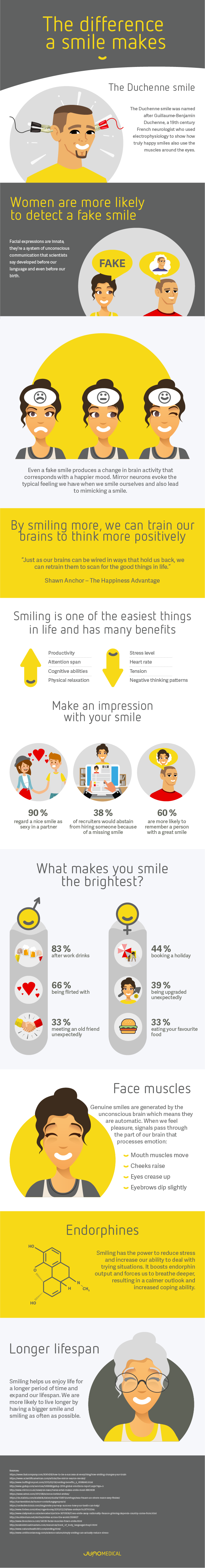

Followers of this blog will be familiar with the seven basic emotions. There are certain emotional expressions that span cultural divides across the planet, such as happiness, anger, and disgust.

Dr. Matsumoto emphasizes only one of these: joy. This is the clearest emotion, as “all other emotions are prone to misunderstanding… but positivity is not usually misinterpreted.” Based on his advice, we should approach intercultural communication sporting a smile and making a pointed effort to learn about their culture.

Pairing this with even a rudimentary understanding of language can also help. Dr. Matsumoto recommends learning basic, positive phrases like “good morning,” or “thank you,” which “go a long way to greasing many interactions.”

Hopefully, Dr. Matsumoto’s advice can be helpful to you! For more tips on how to improve cross cultural communication, check out Humintell’s training packages here and here.

By Humintell Director

By Humintell Director