Believe it or not, the 2024 Presidential Election is right around the corner. And according to a new study out of Denmark, AI may be able to predict your political views.

A team of researchers based in Denmark and Sweden recently conducted a study to see if “deep learning techniques,” like facial recognition technology and predictive analytics can be used on faces to predict a person’s political views.

The study was entitled “Using deep learning to predict ideology from facial photographs: expressions, beauty, and extra-facial information” and published as an open access article in March 2023.

The Methodology

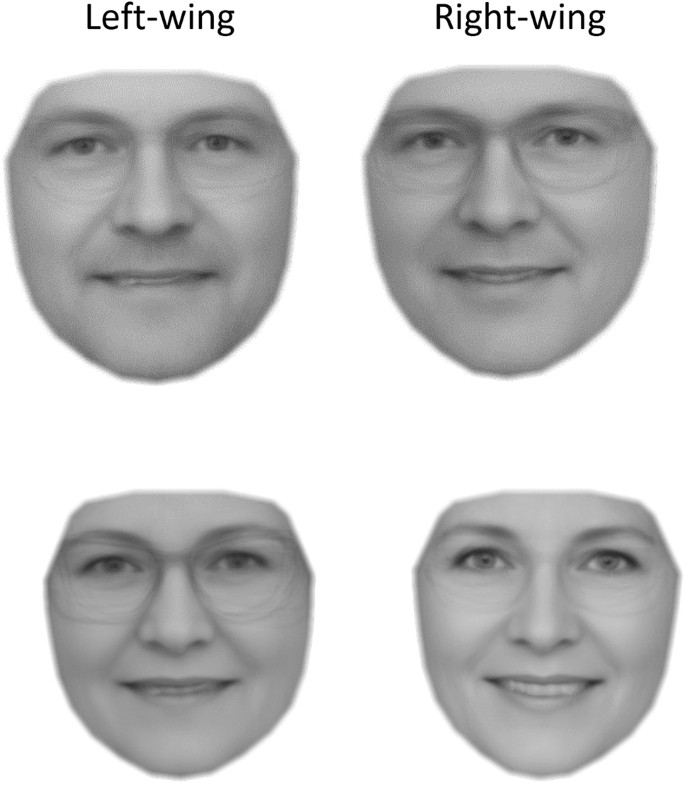

T he researchers used a public dataset of 3,233 images of Danish political candidates who ran for local office and cropped them to only show their faces (see example image to the left).

he researchers used a public dataset of 3,233 images of Danish political candidates who ran for local office and cropped them to only show their faces (see example image to the left).

After that, they applied advanced techniques to assess their facial expressions and a facial beauty database to determine a person’s “beauty score.”

Using these data points, the scientists predicted whether the figures pictured were left-wing or right-wing.

According to Business Insider, “The study found that the tech accurately predicted the political affiliations 61% of time.

The model predicted that conservative candidates “appeared happier than their left-wing counterparts” because of their smiles, whereas liberal candidates were more neutral.

Women who expressed contempt — a facial expression characterized by neutral eyes and one corner of the lips lifted — were linked to more liberal politics by the model.”

In addition, the researchers found that AI correlated the political candidate’s level of attractiveness with their politics.

Women deemed attractive by their beauty scores were predicted to have conservative views, though there was not a similar correlation between mens’ level of attractiveness and right-wing leanings.

The study’s writers say the results of this study, “confirmed the threat to privacy posed by deep learning approaches.”

Attractiveness and Political Ideology

Links between attractiveness and political ideology are nothing new.

One study entitled “Effect of physical attractiveness on political beliefs” examined the relationship between attractiveness and political beliefs.

“more attractive individuals are more likely to identify as conservative and Republican than less physically attractive citizens…results are consistent across datasets and persist when controlling for socioeconomic status and demographics” https://t.co/l1LlQWfjbU pic.twitter.com/TkWnFDRNHF

— Rob Henderson (@robkhenderson) August 8, 2020

As reported in the Guardian, “The researchers took data from the 1972, 1974 and 1976 American National Studies surveys which asked people to evaluate the appearance of others and also explored participants’ political beliefs, income, race, gender, and education.

These results were compared with the Wisconsin Longitudinal study which focused on the physical characteristics of more than 10,000 high school students who were rated by others on their level of attractiveness.”

The results of that study suggested that “more attractive individuals are more likely to report higher levels of political efficacy, identify as conservative, and identify as Republican.”

Facial Recognition Technology and Political Orientation

Similar research suggests that facial recognition technology can predict a person’s political orientation with 72% accuracy.

Similar research suggests that facial recognition technology can predict a person’s political orientation with 72% accuracy.

Published in Scientific Reports one study suggests that facial recognition technology can accurately predict someone’s political stance from their Facebook profile photo.

Michal Kosinski, an associate professor at Stanford University, applied a facial recognition algorithm to 1,085,795 faces obtain from online social media profiles.

Of this dataset, 977,777 came from dating website users in the U.S., UK, and Canada who had self-reported their political orientation.

The other 108,018 faces were from Facebook users in the U.S. who also self-reported their political orientation and additionally completed a 100-item personality test.

The algorithm compared each participant’s facial features to the average facial features of liberals and conservatives. The technology used these similarity measurements to determine the likelihood that a participant was either a conservative or a liberal.

The results showed that the algorithm was able to predict political orientation alarmingly well and with similar accuracy across countries and social media platforms.

Among U.S. Facebook users, this accuracy hit 73%. Among U.S. dating website users, accuracy was 72%. Among dating website users in the UK and Canada, accuracy reached 70% and 71%, respectively.

The post Can AI Tell Your Politics By Looking At Your Face? first appeared on Humintell.

By

By  What are some myths about deception? What are good deception detection techniques? How can auditors build more trust?

What are some myths about deception? What are good deception detection techniques? How can auditors build more trust?