It’s no surprise that deception and politics are intertwined, but are you the person to disentangle them?

The Pew Research Center has issued that very challenge, though in the somewhat lighthearted context of an online quiz. This challenges readers to classify given statements as “factual” or simply “opinions,” but it’s harder than you would think!

In fact, only 26 percent of Americans could correctly identify all the factual statements, and only the slightly higher 35 percent could identify the opinion statements. This is somewhat easier if you are politically engaged and follow the news, but even that’s no guarantee!

Can you tell the difference between factual and opinion news statements?

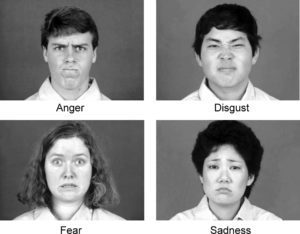

The role of deception in politics is an omnipresent concern. During the election season, Humintell’s Dr. David Matsumoto published an enlightening series of posts discussing the ways in which language and nonverbal behavior can be used to spin the news or conceal a politician’s motives.

Check our Parts One, Two, and Three here, but especially Dr. Matsumoto’s conclusion here!

When understanding how other cultures express emotions, it is almost as important to reflect on our own cultural norms as it is to recognize differing ones.

When understanding how other cultures express emotions, it is almost as important to reflect on our own cultural norms as it is to recognize differing ones. It is almost a common sense view that people living in the United States are much more individualist than those in Japan, but this view may be deeply flawed.

It is almost a common sense view that people living in the United States are much more individualist than those in Japan, but this view may be deeply flawed.